The DBQ, or document-based-question, is a somewhat unusually-formatted timed essay on the AP History Exams: AP US History, AP European History, and AP World History. Because of its unfamiliarity, many students are at a loss as to how to even prepare, let alone how to write a successful DBQ essay on test day.

Never fear! I, the DBQ wizard and master, have a wealth of preparation strategies for you, as well as advice on how to cram everything you need to cover into your limited DBQ writing time on exam day. When you're done reading this guide, you'll know exactly how to write a DBQ.

For a general overview of the DBQ—what it is, its purpose, its format, etc.—see my article "What is a DBQ?"

Table of Contents

What Should My Study Timeline Be?

Establish a Baseline

Foundational Skills

Rubric Breakdown

Take Another Practice DBQ

How Can I Succeed on Test Day?

Reading the Question and Documents

Planning Your Essay

Writing Your Essay

Key Takeaways

What Should My DBQ Study Timeline Be?

Your AP exam study timeline depends on a few things. First, how much time you have to study per week, and how many hours you want to study in total? If you don't have much time per week, start a little earlier; if you will be able to devote a substantial amount of time per week (10-15 hours) to prep, you can wait until later in the year.

One thing to keep in mind, though, is that the earlier you start studying for your AP test, the less material you will have covered in class. Make sure you continually review older material as the school year goes on to keep things fresh in your mind, but in terms of DBQ prep it probably doesn't make sense to start before February or January at the absolute earliest.

Another factor is how much you need to work on. I recommend you complete a baseline DBQ around early February to see where you need to focus your efforts.

If, for example, you got a six out of seven and missed one point for doing further document analysis, you won't need to spend too much time studying how to write a DBQ. Maybe just do a document analysis exercise every few weeks and check in a couple months later with another timed practice DBQ to make sure you've got it.

However, if you got a two or three out of seven, you'll know you have more work to do, and you'll probably want to devote at least an hour or two every week to honing your skills.

The general flow of your preparation should be: take a practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, and so on. How often you take the practice DBQs and how many times you repeat the cycle really depends on how much preparation you need, and how often you want to check your progress. Take practice DBQs often enough that the format stays familiar, but not so much that you've done barely any skills practice in between.

He's ready to start studying!

Preparing for the DBQ

The general preparation process is to diagnose, practice, test, and repeat. First, you'll figure out what you need to work on by establishing a baseline level for your DBQ skills. Then, you'll practice building skills. Finally, you'll take another DBQ to see how you've improved and what you still need to work on.

In this next section, I'll go over the whole process. First, I'll give guidance on how to establish a baseline. Then I'll go over some basic, foundational essay-writing skills and how to build them. After that I'll break down the DBQ rubric. You'll be acing practice DBQs before you know it!

#1: Establish a Baseline

The first thing you need to do is to establish a baseline—figure out where you are at with respect to your DBQ skills. This will let you know where you need to focus your preparation efforts.

To do this, you will take a timed, practice DBQ and have a trusted teacher or advisor grade it according to the appropriate rubric.

AP US History

For the AP US History DBQ, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time.

A selection of practice questions from the exam can be found online at the College Board, including a DBQ. (Go to page 136 in the linked document for the practice prompt.)

If you've already seen this practice question, perhaps in class, you might use the 2015 DBQ question.

Other available College Board DBQs are going to be in the old format (find them in the "Free-Response Questions" documents). This is fine if you need to use them, but be sure to use the new rubric (which is out of seven points, rather than nine) to grade.

I advise you to save all these links, or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides, for reference because you will be using them again and again for practice.

AP European History

For this exam, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time.The College Board has provided practice questions for the exam, including a DBQ (see page 200 in the linked document).

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2016 DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History exam. Just be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board. (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

I advise you to save all these links (or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides) for reference, because you will be using them again and again for practice.

Who knows—maybe this will be one of your documents!

AP World History

For this exam, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time. As for the other two history exams, the College Board has provided practice questions. See page 166 for the DBQ.

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2017 World History DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History and AP European History exams. So be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board. (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

I advise you to save all these links (or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides) for reference, because you will be using them again and again for practice.

Finding a Trusted Advisor to Look at Your Papers

A history teacher would be a great resource, but if they are not available to you in this capacity, here are some other ideas:

- An English teacher.

- Ask a librarian at your school or public library! If they can't help you, they may be able to direct you to resources who can.

- You could also ask a school guidance counselor to direct you to in-school resources you could use.

- A tutor. This is especially helpful if they are familiar with the test, although even if they aren't, they can still advise—the DBQ is mostly testing academic writing skills under pressure.

- Your parent(s)! Again, ideally your trusted advisor will be familiar with the AP, but if you have used your parents for writing help in the past they can also assist here.

- You might try an older friend who has already taken the exam and did well...although bear in mind that some people are better at doing than scoring and/or explaining!

Can I Prepare For My Baseline?

If you know nothing about the DBQ and you'd like to do a little basic familiarization before you establish your baseline, that's completely fine. There's no point in taking a practice exam if you are going to panic and muddle your way through it; it won't give a useful picture of your skills.

For a basic orientation, check out my article for a basic introduction to the DBQ including DBQ format.

If you want to look at one or two sample essays, see my article for a list of DBQ example essay resources. Keep in mind that you should use a fresh prompt you haven't seen to establish your baseline, though, so if you do look at samples don't use those prompts to set your baseline.

I would also check out this page about the various "task" words associated with AP essay questions. This page was created primarily for the AP European History Long Essay question, but the definitions are still useful for the DBQ on all the history exams, particularly since these are the definitions provided by the College Board.

Once you feel oriented, take your practice exam!

Don't worry if you don't do well on your first practice! That's what studying is for. The point of establishing a baseline is not to make you feel bad, but to empower you to focus your efforts on the areas you need to work on. Even if you need to work on all the areas, that is completely fine and doable! Every skill you need for the DBQ can be built.

In the following section, we'll go over these skills and how to build them for each exam.

You need a stronger foundation than this sand castle.

#2: Develop Foundational Skills

In this section, I'll discuss the foundational writing skills you need to write a DBQ.

I'll start with some general information on crafting an effective thesis, since this is a skill you will need for any DBQ exam (and for your entire academic life). Then, I'll go over outlining essays, with some sample outline ideas for the DBQ. After I'll touch on time management. Finally, I'll briefly discuss how to non-awkwardly integrate information from your documents into your writing.

It sounds like a lot, but not only are these skills vital to your academic career in general, you probably already have the basic building blocks to master them in your arsenal!

Writing An Effective Thesis

Writing a good thesis is a skill you will need to develop for all your DBQs, and for any essay you write, on the AP or otherwise.

Here are some general rules as to what makes a good thesis:

-

A good thesis does more than just restate the prompt.

-

Let's say our class prompt is: "Analyze the primary factors that led to the French Revolution."

-

Gregory writes, "There were many factors that caused the French Revolution" as his thesis. This is not an effective thesis. All it does is vaguely restate the prompt.

-

-

A good thesis makes a plausible claim that you can defend in an essay-length piece of writing.

-

Maybe Karen writes, "Marie Antoinette caused the French Revolution when she said ‘Let them eat cake' because it made people mad."

-

This is not an effective thesis, either. For one thing, Marie Antoinette never said that. More importantly, how are you going to write an entire essay on how one offhand comment by Marie Antoinette caused the entire Revolution? This is both implausible and overly simplistic.

-

-

A good thesis answers the question.

-

If LaToya writes, "The Reign of Terror led to the ultimate demise of the French Revolution and ultimately paved the way for Napoleon Bonaparte to seize control of France," she may be making a reasonable, defensible claim, but it doesn't answer the question, which is not about what happened after the Revolution, but what caused it!

-

-

A good thesis makes it clear where you are going in your essay.

-

Let's say Juan writes, "The French Revolution, while caused by a variety of political, social, and economic factors, was primarily incited by the emergence of the highly educated Bourgeois class." This thesis provides a mini-roadmap for the entire essay, laying out that Juan is going to discuss the political, social, and economic factors that led to the Revolution, in that order, and that he will argue that the members of the Bourgeois class were the ultimate inciters of the Revolution.

-

This is a great thesis! It answers the question, makes an overarching point, and provides a clear idea of what the writer is going to discuss in the essay.

-

To review: a good thesis makes a claim, responds to the prompt, and lays out what you will discuss in your essay.

If you feel like you have trouble telling the difference between a good thesis and a not-so-good one, here are a few resources you can consult:

-

This site from SUNY Empire has an exercise in choosing the best thesis from several options. It's meant for research papers, but the general rules as to what makes a good thesis apply.

-

About.com has another exercise in choosing thesis statements specifically for short essays. Note, however, that most of the correct answers here would be "good" thesis statements as opposed to "super" thesis statements.

- This guide from the University of Iowa provides some really helpful tips on writing a thesis for a history paper.

So how do you practice your thesis statement skills for the DBQ?

While you should definitely practice looking at DBQ questions and documents and writing a thesis in response to those, you may also find it useful to write some practice thesis statements in response to the Free-Response Questions. While you won't be taking any documents into account in your argument for the Free-Response Questions, it's good practice on how to construct an effective thesis in general.

You could even try writing multiple thesis statements in response to the same prompt! It is a great exercise to see how you could approach the prompt from different angles. Time yourself for 5-10 minutes to mimic the time pressure of the AP exam.

If possible, have a trusted advisor or friend look over your practice statements and give you feedback. Barring that, looking over the scoring guidelines for old prompts (accessible from the same page on the College Board where past free-response questions can be found) will provide you with useful tips on what might make a good thesis in response to a given prompt.

Once you can write a thesis, you need to be able to support it—that's where outlining comes in!

This is not a good outline.

Outlining and Formatting Your Essay

You may be the greatest document analyst and thesis-writer in the world, but if you don't know how to put it all together in a DBQ essay outline, you won't be able to write a cohesive, high-scoring essay on test day.

A good outline will clearly lay out your thesis and how you are going to support that thesis in your body paragraphs. It will keep your writing organized and prevent you from forgetting anything you want to mention!

For some general tips on writing outlines, this page from Roane State has some useful information. While the general principles of outlining an essay hold, the DBQ format is going to have its own unique outlining considerations.To that end, I've provided some brief sample outlines that will help you hit all the important points.

Sample DBQ Outline

- Introduction

- Thesis. The most important part of your intro!

- Body 1 - contextual information

- Any outside historical/contextual information

- Body 2 - First point

- Documents & analysis that support the first point

- If three body paragraphs: use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Body 3 - Second point

- Documents & analysis that support the second point

- Use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Be sure to mention your outside example if you have not done so yet!

- Body 4 (optional) - Third point

- Documents and analysis that support third point

- Conclusion

- Re-state thesis

- Draw a comparison to another time period or situation (synthesis)

Depending on your number of body paragraphs and your main points, you may include different numbers of documents in each paragraph, or switch around where you place your contextual information, your outside example, or your synthesis.

There's no one right way to outline, just so long as each of your body paragraphs has a clear point that you support with documents, and you remember to do a deeper analysis on four documents, bring in outside historical information, and make a comparison to another historical situation or time (you will see these last points further explained in the rubric breakdown).

Of course, all the organizational skills in the world won't help you if you can't write your entire essay in the time allotted. The next section will cover time management skills.

You can be as organized as this library!

Time Management Skills for Essay Writing

Do you know all of your essay-writing skills, but just can't get a DBQ essay together in a 15-minute planning period and 40 minutes of writing?

There could be a few things at play here:

-

Do you find yourself spending a lot of time staring at a blank paper?

-

If you feel like you don't know where to start, spend one-two minutes brainstorming as soon as you read the question and the documents. Write anything here—don't censor yourself. No one will look at those notes but you!

-

After you've brainstormed for a bit, try to organize those thoughts into a thesis, and then into body paragraphs. It's better to start working and change things around than to waste time agonizing that you don't know the perfect thing to say.

-

-

Are you too anxious to start writing, or does anxiety distract you in the middle of your writing time? Do you just feel overwhelmed?

-

Sounds like test anxiety. Lots of people have this. (Including me! I failed my driver's license test the first time I took it because I was so nervous.)

-

You might talk to a guidance counselor about your anxiety. They will be able to provide advice and direct you to resources you can use.

-

There are also some valuable test anxiety resources online: try our guide to mindfulness (it's focused on the SAT, but the same concepts apply on any high-pressure test) and check out tips from Minnesota State University, these strategies from TeensHealth, or this plan for reducing anxiety from West Virginia University.

-

-

Are you only two thirds of the way through your essay when 40 minutes have passed?

-

You are probably spending too long on your outline, biting off more than you can chew, or both.

-

If you find yourself spending 20+ minutes outlining, you need to practice bringing down your outline time. Remember, an outline is just a guide for your essay—it is fine to switch things around as you are writing. It doesn't need to be perfect. To cut down on your outline time, practice just outlining for shorter and shorter time intervals. When you can write one in 20 minutes, bring it down to 18, then down to 16.

-

You may also be trying to cover too much in your paper. If you have five body paragraphs, you need to scale things back to three. If you are spending twenty minutes writing two paragraphs of contextual information, you need to trim it down to a few relevant sentences. Be mindful of where you are spending a lot of time, and target those areas.

-

-

You don't know the problem—you just can't get it done!

-

If you can't exactly pinpoint what's taking you so long, I advise you to simply practice writing DBQs in less and less time. Start with 20 minutes for your outline and 50 for your essay, (or longer, if you need). Then when you can do it in 20 and 50, move back to 18 minutes and 45 for writing, then to 15 and 40.

-

You absolutely can learn to manage your time effectively so that you can write a great DBQ in the time allotted. On to the next skill!

Integrating Citations

The final skill that isn't explicitly covered in the rubric, but will make a big difference in your essay quality, is integrating document citations into your essay. In other words, how do you reference the information in the documents in a clear, non-awkward way?

It is usually better to use the author or title of the document to identify a document instead of writing "Document A." So instead of writing "Document A describes the riot as...," you might say, "In Sven Svenson's description of the riot…"

When you quote a document directly without otherwise identifying it, you may want to include a parenthetical citation. For example, you might write, "The strikers were described as ‘valiant and true' by the working class citizens of the city (Document E)."

Now that we've reviewed the essential, foundational skills of the DBQ, I'll move into the rubric breakdowns. We'll discuss each skill the AP graders will be looking for when they score your exam. All of the history exams share a DBQ rubric, so the guidelines are identical.

Don't worry, you won't need a magnifying glass to examine the rubric.

#3: Learn the DBQ Rubric

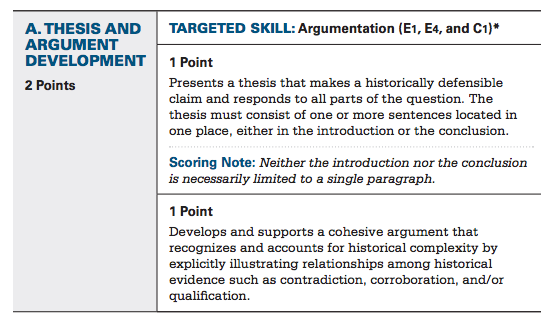

The DBQ rubric has four sections for a total of seven points.

Part A: Thesis - 2 Points

One point is for having a thesis that works and is historically defensible. This just means that your thesis can be reasonably supported by the documents and historical fact. So please don't make the main point of your essay that JFK was a member of the Illuminati or that Pope Urban II was an alien.

Per the College Board, your thesis needs to be located in your introduction or your conclusion. You've probably been taught to place your thesis in your intro, so stick with what you're used to. Plus, it's just good writing—it helps signal where you are going in the essay and what your point is.

You can receive another point for having a super thesis.

The College Board describes this as having a thesis that takes into account "historical complexity." Historical complexity is really just the idea that historical evidence does not always agree about everything, and that there are reasons for agreement, disagreement, etc.

How will you know whether the historical evidence agrees or disagrees? The documents! Suppose you are responding to a prompt about women's suffrage (suffrage is the right to vote, for those of you who haven't gotten to that unit in class yet):

"Analyze the responses to the women's suffrage movement in the United States."

Included among your documents, you have a letter from a suffragette passionately explaining why she feels women should have the vote, a copy of a suffragette's speech at a women's meeting, a letter from one congressman to another debating the pros and cons of suffrage, and a political cartoon displaying the death of society and the end of the ‘natural' order at the hands of female voters.

A simple but effective thesis might be something like,

"Though ultimately successful, the women's suffrage movement sharply divided the country between those who believed women's suffrage was unnatural and those who believed it was an inherent right of women."

This is good: it answers the question and clearly states the two responses to suffrage that are going to be analyzed in the essay.

A super thesis, however, would take the relationships between the documents (and the people behind the documents!) into account.

It might be something like,

"The dramatic contrast between those who responded in favor of women's suffrage and those who fought against it revealed a fundamental rift in American society centered on the role of women—whether women were ‘naturally' meant to be socially and civilly subordinate to men, or whether they were in fact equals."

This is a "super" thesis because it gets into the specifics of the relationship between historical factors and shows the broader picture—that is, what responses to women's suffrage revealed about the role of women in the United States overall.

It goes beyond just analyzing the specific issues to a "so what"? It doesn't just take a position about history, it tells the reader why they should care. In this case, our super thesis tells us that the reader should care about women's suffrage because the issue reveals a fundamental conflict in America over the position of women in society.

Part B: Document Analysis - 2 Points

One point for using six or seven of the documents in your essay to support your argument. Easy-peasy! However, make sure you aren't just summarizing documents in a list, but are tying them back to the main points of your paragraphs.

It's best to avoid writing things like, "Document A says X, and Document B says Y, and Document C says Z." Instead, you might write something like, "The anonymous author of Document C expresses his support and admiration for the suffragettes but also expresses fear that giving women the right to vote will lead to conflict in the home, highlighting the common fear that women's suffrage would lead to upheaval in women's traditional role in society."

Any summarizing should be connected a point. Essentially, any explanation of what a document says needs to be tied to a "so what?" If it's not clear to you why what you are writing about a document is related to your main point, it's not going to be clear to the AP grader.

You can get an additional point here for doing further analysis on 4 of the documents. This further analysis could be in any of these 4 areas:

-

Author's point of view - Why does the author think the way that they do? What is their position in society and how does this influence what they are saying?

-

Author's purpose - Why is the author writing what they are writing? What are they trying to convince their audience of?

-

Historical context - What broader historical facts are relevant to this document?

-

Audience - Who is the intended audience for this document? Who is the author addressing or trying to convince?

Be sure to tie any further analysis back to your main argument! And remember, you only have to do this for four documents for full credit, but it's fine to do it for more if you can.

Practicing Document Analysis

So how do you practice document analysis? By analyzing documents!

Luckily for AP test takers everywhere, New York State has an exam called the Regents Exam that has its own DBQ section. Before they write the essay, however, New York students have to answer short answer questions about the documents.

Answering Regents exam DBQ short-answer questions is good practice for basic document analysis. While most of the questions are pretty basic, it's a good warm-up in terms of thinking more deeply about the documents and how to use them. This set of Regent-style DBQs from the Teacher's Project are mostly about US History, but the practice could be good for other tests too.

This prompt from the Morningside center also has some good document comprehensions questions about a US-History based prompt.

Note: While the document short-answer questions are useful for thinking about basic document analysis, I wouldn't advise completing entire Regents exam DBQ essay prompts for practice, because the format and rubric are both somewhat different from the AP.

Your AP history textbook may also have documents with questions that you can use to practice. Flip around in there!

This otter is ready to swim in the waters of the DBQ.

When you want to do a deeper dive on the documents, you can also pull out those old College Board DBQ prompts.

-

Read the documents carefully. Write down everything that comes to your attention. Do further analysis—author's point of view, purpose, audience, and historical context—on all the documents for practice, even though you will only need to do additional analysis on four on test day. Of course, you might not be able to do all kinds of further analysis on things like maps and graphs, which is fine.

-

You might also try thinking about how you would arrange those observations in an argument, or even try writing a practice outline! This exercise would combine your thesis and document-analysis skills practice.

-

When you've analyzed everything you can possibly think of for all the documents, pull up the Scoring Guide for that prompt. It helpfully has an entire list of analysis points for each document.

-

Consider what they identified that you missed.

-

Do you seem way off-base in your interpretation? If so, how did it happen?

-

Part C: Using Evidence Beyond the Documents - 2 Points

Don't be freaked out by the fact that this is two points!

One point is just for context—if you can locate the issue within its broader historical situation. You do need to write several sentences to a paragraph about it, but don't stress; all you really need to know to be able to get this point is information about major historical trends over time, and you will need to know this anyways for the multiple choice section. If the question is about the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, for example, be sure to include some of the general information you know about the Great Depression! Boom. Contextualized.

The other point is for naming a specific, relevant example in your essay that does not appear in the documents.

To practice your outside information skills, pull up your College Board prompts!

-

Read through the prompt and documents and then write down all of the contextualizing facts and as many specific examples as you can think of.

-

I advise timing yourself—maybe 5-10 minutes to read the documents and prompt and list your outside knowledge—to imitate the time pressure of the DBQ.

-

When you've exhausted your knowledge, make sure to fact-check your examples and your contextual information! You don't want to use incorrect information on test day.

-

If you can't remember any examples or contextual information about that topic, look some up! This will help fill in holes in your knowledge.

Part D: Synthesis - 1 Point

All you need to do for synthesis is relate your argument about this specific time period to a different time period, geographical area, historical movement, etc. It is probably easiest to do this in the conclusion of the essay. If your essay is about the Great Depression, you might relate it to the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

You do need to do more than just mention your synthesis connection. You need to make it meaningful. How are the two things you are comparing similar? What does one reveal about the other? Is there a key difference that highlights something important?

To practice your synthesis skills—you guessed it—pull up your College Board prompts!

- Read through the prompt and documents and then identify what historical connections you could make for your synthesis point. Be sure to write a few words on why the connection is significant!

- A great way to make sure that your synthesis connection makes sense is to explain it to someone else. If you explain what you think the connection is and they get it, you're probably on the right track.

- You can also look at sample responses and the scoring guide for the old prompts to see what other connections students and AP graders made.

That's a wrap on the rubric! Let's move on to skill-building strategy.

Don't let the DBQ turn you into a dissolving ghost-person, though.

#4: Focus on Your Skill-Building Strategy

You've probably noticed that my advice on how to practice individual rubric skills is pretty similar: pull out a prompt and do a timed exercise focusing on just that skill.

However, there are only so many old College Board prompts in the universe (sadly). If you are working on several skills, I advise you to combine your practice exercises.

What do I mean? Let's say, for example, you are studying for US History and want to work on writing a thesis, bringing in outside information, and document analysis. Set your timer for 15-20 minutes, pull up a prompt, and:

- Write 2-3 potential thesis statements in response to the prompt

- Write all the contextual historical information you can think of, and a few specific examples

- Write down analysis notes on all the documents.

Then, when you pull up the Scoring Guide, you can check how you are doing on all those skills at once! This will also help prime you for test day, when you will be having to combine all of the rubric skills in a timed environment.

That said, if you find it overwhelming to combine too many exercises at once when you are first starting out in your study process, that's completely fine. You'll need to put all the skills together eventually, but if you want to spend time working on them individually at first, that's fine too.

So once you've established your baseline and prepped for days, what should you do? It's time to take another practice DBQ to see how you've improved!

I know you're tired, but you can do it!

#5: Take Another Practice DBQ

So, you established a baseline, identified the skills you need to work on, and practiced writing a thesis statement and analyzing documents for hours. What now?

Take another timed, practice DBQ from a prompt you haven't seen before to check how you've improved. Recruit your same trusted advisor to grade your exam and give feedback. After, work on any skills that still need to be honed.

Repeat this process as necessary, until you are consistently scoring your goal score. Then you just need to make sure you maintain your skills until test day by doing an occasional practice DBQ.

Eventually, test day will come—read on for my DBQ-test-taking tips.

How Can I Succeed On DBQ Test Day?

Once you've prepped your brains out, you still have to take the test! I know, I know. But I've got some advice on how to make sure all of your hard work pays off on test day—both some general tips and some specific advice on how to write a DBQ.

#1: General Test-Taking Tips

Most of these are probably tips you've heard before, but they bear repeating:

-

Get a good night's sleep for the two nights preceding the exam. This will keep your memory sharp!

-

Eat a good breakfast (and lunch, if the exam is in the afternoon) before the exam with protein and whole grains. This will keep your blood sugar from crashing and making you tired during the exam.

-

Don't study the night before the exam if you can help it. Instead, do something relaxing. You've been preparing, and you will have an easier time on exam day if you aren't stressed from trying to cram the night before.

This dude knows he needs to get a good night's rest!

#2: DBQ Plan and Strategies

Below I've laid out how to use your time during the DBQ exam. I'll provide tips on reading the question and docs, planning your essay, and writing!

Be sure to keep an eye on the clock throughout so you can track your general progress.

Reading the Question and the Documents: 5-6 min

First thing's first: read the question carefully, two or even three times. You may want to circle the task words ("analyze," "describe," "evaluate," "compare") to make sure they stand out.

You could also quickly jot down some contextual information you already know before moving on to the documents, but if you can't remember any right then, move on to the docs and let them jog your memory.

It's fine to have a general idea of a thesis after you read the question, but if you don't, move on to the docs and let them guide you in the right direction.

Next, move on to the documents. Mark them as you read—circle things that seem important, jot thoughts and notes in the margins.

After you've passed over the documents once, you should choose the four documents you are going to analyze more deeply and read them again. You probably won't be analyzing the author's purpose for sources like maps and charts. Good choices are documents in which the author's social or political position and stake in the issue at hand are clear.

Get ready to go down the document rabbit hole.

Planning Your Essay: 9-11 min

Once you've read the question and you have preliminary notes on the documents, it's time to start working on a thesis. If you still aren't sure what to talk about, spend a minute or so brainstorming. Write down themes and concepts that seem important and create a thesis from those. Remember, your thesis needs to answer the question and make a claim!

When you've got a thesis, it's time to work on an outline. Once you've got some appropriate topics for your body paragraphs, use your notes on the documents to populate your outline. Which documents support which ideas? You don't need to use every little thought you had about the document when you read it, but you should be sure to use every document.

Here's three things to make sure of:

-

Make sure your outline notes where you are going to include your contextual information (often placed in the first body paragraph, but this is up to you), your specific example (likely in one of the body paragraphs), and your synthesis (the conclusion is a good place for this).

-

Make sure you've also integrated the four documents you are going to further analyze and how to analyze them.

-

Make sure you use all the documents! I can't stress this enough. Take a quick pass over your outline and the docs and make sure all of the docs appear in your outline.

If you go over the planning time a couple of minutes, it's not the end of the world. This probably just means you have a really thorough outline! But be ready to write pretty fast.

Writing the Essay - 45 min

If you have a good outline, the hard part is out of the way! You just need to make sure you get all of your great ideas down in the test booklet.

Don't get too bogged down in writing a super-exciting introduction. You won't get points for it, so trying to be fancy will just waste time. Spend maybe one or two sentences introducing the issue, then get right to your thesis.

For your body paragraphs, make sure your topic sentences clearly state the point of the paragraph. Then you can get right into your evidence and your document analysis.

As you write, make sure to keep an eye on the time. You want to be a little more than halfway through at the 20-minute mark of the writing period, so you have a couple minutes to go back and edit your essay at the end.

Keep in mind that it's more important to clearly lay out your argument than to use flowery language. Sentences that are shorter and to the point are completely fine.

If you are short on time, the conclusion is the least important part of your essay. Even just one sentence to wrap things up is fine just so long as you've hit all the points you need to (i.e. don't skip your conclusion if you still need to put in your synthesis example).

When you are done, make one last past through your essay. Make sure you included everything that was in your outline and hit all the rubric skills! Then take a deep breath and pat yourself on the back.

You did it!! Have a cupcake to celebrate.

Key Tips for How to Write a DBQ

I realize I've bombarded you with information, so here are the key points to take away:

-

Remember the drill for prep: establish a baseline, build skills, take another practice DBQ, repeat skill-building as necessary.

-

Make sure that you know the rubric inside and out so you will remember to hit all the necessary points on test day! It's easy to lose points just for forgetting something like your synthesis point.

-

On test day, keep yourself on track time-wise!

This may seem like a lot, but you can learn how to ace your DBQ! With a combination of preparation and good test-taking strategy, you will get the score you're aiming for. The more you practice, the more natural it will seem, until every DBQ is a breeze.

What's Next?

If you want more information about the DBQ, see my introductory guide to the DBQ.

Haven't registered for your AP test yet? See our article for help registering for AP exams.

For more on studying for the AP US History exam, check out the best AP US History notes to study with.

Studying for World History? See these AP World History study tips from one of our experts.