Many students dream of getting into elite schools like Harvard, Yale, Princeton, or Stanford, but how exactly to accomplish this is often a mystery. Lots of unhelpful and vague advice abounds, especially from people who have never gained admission to these schools.

In high school, I got into every school I applied to, including Harvard, Princeton, MIT, and Stanford, and I attended Harvard for college. I also learned a lot about my classmates and the dynamics of college admissions in ways that were never clear to me in high school. Now, I'm sharing this expertise with you.

I've written the most comprehensive guide to getting into top schools. I'm going to explain in detail what admissions officers at Ivy League schools are really looking for in your application. More importantly, I'm going to share an actionable framework you can use to build the most compelling application that's unique to you.

How to Get Into the Ivy League: Brief Overview

If there's one central takeaway from this article, it's that most students are spending their time on entirely the wrong things because they have an incorrect view of what top colleges are really looking for.

If you're struggling to stay afloat with a ton of AP classes in subjects you don't care about, a sports team, SAT/ACT prep, and volunteering, you're hurting yourself—and are probably incredibly unhappy, too. We'll drill down into exactly why this is such a huge mistake.

Here is an overview of the major sections in this article:

- Part 1: Why Schools Exist and What They Want to Accomplish

- Part 2: What Types of Students Ivy League Schools Want to Admit and Why

- Part 3: Busting a Myth: "School Admissions Are a Crapshoot for Everyone"

- Part 4: What Does All of This Mean for Your Application?

- Part 5: OK—So Now What Do I Actually Do, Allen?

- Bonus: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

This article is long and detailed, but I strongly believe it's well worth your time. These are all the lessons I wish I had known when I was in high school myself. So I suggest you read it through fully at least once.

When you finish reading this guide, it is my hope that you'll dramatically change your beliefs about how to get into Stanford, Harvard, and other Ivy League-level schools.

Important Disclaimers

Before we dive in, I need to get a few things out of the way. My advice in this article is blunt and pragmatic, and I have strong opinions. Even if one of my points rubs you the wrong way, I don't want one bad apple to spoil the bunch—you might end up ignoring advice that would otherwise be helpful. So let me clear up some common misconceptions about what I'm saying.

First of all, it's completely OK if you don't go to Harvard. I wish I were joking about having to tell people this. Attending Harvard or Yale or Stanford doesn't guarantee you success in life! Lots of students who go to these schools end up aimless, and many more who don't go to top schools end up accomplishing a lot.

More than anything, your success in life is up to you—not your environment or factors out of your control. The school you go to cannot guarantee your own success. So whether you get into a top school or not, it's only the beginning of a long road, and what happens during your journey is almost entirely up to you. (That said, I believe going to a top school gives you huge advantages, particularly in the availability of resources and strength of the community. If I had to do it all over, I would have 100% gone to Harvard again. More on this later.)

I don't believe that getting into a top school like Stanford or Duke should be the singular goal of high school students. Happiness and fulfillment are really important and are rarely taken seriously enough. Luckily, with the approach to admissions that I explain below, you'll be able to explore your passions while also building a strong application.

This article is a guide to admissions to the top schools in the country. To be explicit, I include in this the most selective schools in the Ivy League (consisting of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and Columbia) as well as Stanford, MIT, Duke, and Caltech. Generally speaking, these are the top 10 schools according to US News and have admissions rates below 10%. Following this guide is really helpful for these ultra-selective schools and important for raising your chances of admission.

There's a second group of high-quality schools for which admissions is relatively easier (Dartmouth, Johns Hopkins, Northwestern, Washington University in St. Louis, Cornell, Brown, Notre Dame, Vanderbilt, Rice, UC Berkeley—ranked #11-18 in US News). If these are your target schools and you follow the advice in this guide, you will absolutely blow away admissions at this latter group and get accepted to every one of them. Big claims, I know, but I stand by my advice here—you'll see.

More than a guide on how to get into Stanford or MIT, this is really a guide on how to explore your passion and structure your life around it. I believe that getting into schools is really just a positive consequence of doing things you're sincerely interested in. Keep this in mind as you read on. As you'll see, trying to do things only for the sake of getting into a top school can be counterproductive and burdensome.

Throughout this article, I'm going to sound a bit elitist. For example, I'm going to refer to what it takes for you to be "world class" and what it means to be "mediocre." This might sound distasteful, as it seems like I'm judging some efforts to be more worthwhile than others. Try not to be turned off by this. Michael Phelps is a world-class swimmer, and I am a terribly mediocre one. Facts are facts, and I'm just presenting how admissions officers will think about comparing you with the 30,000 other applicants from the rest of the world.

I founded a company called PrepScholar. We create online SAT/ACT prep programs that adapt to your strengths and weaknesses. I believe we've created the best prep program available, and if you want to raise your SAT/ACT score, I encourage you to check us out.

I want to emphasize, though, that you do not need to buy a prep program to get a great SAT or ACT score. Moreover, the advice in this guide has little to do with my company. But if you're aren't sure what to study and agree with our unique approach to test prep, our program may be a great fit for you.

Lastly, this article is not a reductionist magic guide on how to get into Stanford or MIT. There are no easy hidden tricks or shortcuts. There is no sequence of steps you can follow to guarantee your personal success. It takes a lot of hard work, passion, and some luck.

But if it weren't hard, then getting into these schools wouldn't be such a valuable accomplishment. Most students who read this guide won't be able to implement it fully, but you should at least take key elements from it to change how you view your college admissions path.

With all that said, I hope you can take what I say below seriously and learn a lot about how colleges think about admissions. If you disagree with anything fundamental below, let me know in a comment. I strongly believe in what I'm saying, and most of my friends and colleagues who went to top schools would agree with this guide, too.

Part 1: Why Schools Exist and What They Want to Accomplish

To fully understand my points below on how to get into Yale and similar schools, we need to first start at the highest level: what do top schools hope to accomplish by existing? This will give us clues as to how a school decides what types of students it'll admit.

All top schools like Harvard, UPenn, and Duke are nonprofits, which means that unlike companies like Starbucks, they don't exist to create profits for shareholders.

But they do something similar: they aim to create as much value as they can in the world. Value can come in a lot of forms.

A common one you hear about is research. Through research by faculty members, schools push the boundaries of human knowledge and contribute to new inventions and theories that can dramatically improve human lives. If you've ever heard a news story saying something like, "A team at Stanford today reported that they found a new treatment for pancreatic cancer," you can bet that Stanford's darn proud of that team.

Another one is through services. Universities often organize programs to consult with national governments or assist nonprofits. A third way of creating value is by publishing books and disseminating research information. The list goes on and on.

But here's one final, huge way schools create value: by educating students who then go on to do great things in the world.

Do you know where Bill Gates went to college? You've probably heard it was Harvard (even though he dropped out). Don't you think Harvard is thrilled to be associated with Bill Gates so publicly, and to be part of his lore?

How about Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the founders of Google? You might have heard that they went to Stanford. And President Barack Obama went to Columbia as an undergrad and Harvard for law school.

Every single school has alumni who make their schools proud. (For example, who can you think of from the University of Chicago or Princeton?) By accomplishing great things in their lives, these alumni carry forward the flags of their alma maters, and their schools then get associated with their accomplishments.

Think of schools like parents and students as their children. The parents provide a nurturing environment for their children who will eventually go on to do great things. The parents are proud whenever the children accomplish anything noteworthy. (And if the children make it big, they might give some money back to their parents.)

To see proof of this in action, visit the news office website of any school. All schools publicize the world-changing things that are happening at the school and by its graduates.

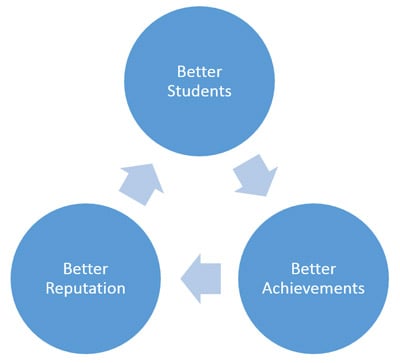

Why do they do this? Because it generates positive feedback loops (remember this from biology?)—aka virtuous cycles. The better the achievements at a school, the better the reputation it has. The better the reputation, the more funding it gets and the better the students who want to attend. The better the students, the better the achievements the school creates. And this continues perpetually so that places like Harvard will likely remain at the top of the education game for a very long time.

We know that schools like Princeton and MIT care about creating as much value as they can, including educating their students. Now for the important question: what does this mean about what schools look for in their next class of freshmen?

Part 2: What Types of Students Ivy League Schools Want to Admit and Why

Let's cut to the chase. Schools are looking for two main qualities in applicants:

- Students who are going to accomplish world-changing things.

- Students who are going to contribute positively to their communities while in college and help other students accomplish great things as well.

That's essentially it.

For every student who enters Harvard or Stanford, the school hopes that he or she will go on to change the world. Again, this can be in a multitude of ways. The student might start the next huge company. She might join a nonprofit and manage a large global health initiative. He might write a novel that wins the Pulitzer Prize. He might even become a great parent to children who will then also go on to do great things.

Here's some proof of this from William R. Fitzsimmons, long-time Dean of Admissions at Harvard College:

"Each year we admit about 2,100 applicants. We like to think that all of them have strong personal qualities and character, that they will educate and inspire their classmates over the four years of college, and that they will make a significant difference in the world after they leave Harvard."

This, of course, is hard to predict when you're just 17 years old. You've barely developed, you don't know exactly what you want to do with your life, and you have a lot of room to grow. But the college application process, as it's designed now, is the best way that colleges have to predict which students are going to accomplish great things.

Your job is to convince the school that you're that person.

This naturally leads us to our first of four questions:

#1: How Do You Predict Who's Going to Change the World?

This is the challenge that all colleges face. Based on the first 17 years of your life, top colleges like Stanford and UChicago want to determine the potential you have to make an impact throughout the rest of your life.

In trying to do this, top colleges adhere to one golden rule: the best predictor of future achievement is past achievement. If you make deep achievements as a high school student, in the college's eyes you're showing that you're capable of achieving great things in the future.

This rule actually holds true in a lot of scenarios outside college admissions. In college football, for example, the Heisman trophy is given annually to the top player. Then, in the NFL draft, Heisman trophy winners are often picked in the first round—in other words, they've proven that they have a huge likelihood of succeeding.

The same goes with decisions you might make in your everyday life. If you're looking for an orthodontist to straighten your teeth, you're more likely to choose someone who has years of making happy smiles. Likewise, you'd probably avoid the rookie dentist just out of dental school who doesn't have a lot of experience and positive results yet.

The point of your application is to convince the school that, based on your achievements so far, you are going to continue succeeding and achieving great things in college and beyond.

Of course, this system isn't perfect—the past doesn't always predict the future. Tom Brady, one of the best football quarterbacks of all time, was a no-name when he was drafted in 2000. He didn't have a standout college football history, and he was drafted as the 199th pick in the sixth round. So even though you might not have a stellar college application, you could still achieve great things in your career.

Pretty much every football team wishes they'd drafted Tom Brady.

Colleges do make mistakes, but, by and large, they try to adhere to this rule most of the time to predict future success. Therefore, to get into a top school, you need to demonstrate the ability to succeed in the future by achieving great things now.

This idea might not be new to you: "Duh, Allen—of course Harvard wants to admit students who accomplish great things!"

But most likely you're making a mistake in how you demonstrate that you are both world class and capable of accomplishing great things. Most students tackle this in entirely the wrong way; they try to be "well rounded," thinking this is what colleges want to see.

It's a big mistake.

#2: What Is the Critical Flaw With Being Well Rounded?

Most students aiming for top schools make the huge mistake of trying to be "well rounded." When I was in high school, I heard this refrain over and over and over again, from older students and teachers to counselors and supposed "college admissions experts." I'm sure you've heard this phrase, too.

The typical student who wants to be well rounded will try to demonstrate some competency in a variety of skills. She'll learn an instrument, play a JV sport, aim for straight As, score highly on tests, volunteer for dozens of hours at a hospital, and participate in a few clubs.

In these students' minds, they're telling their schools, "I can do everything! Whatever I set my mind to, I can learn to do a pretty good job. This means I'll be successful in the future!"

This is wrong. The world doesn't see it this way, colleges like Yale and MIT generally don't see it this way, and far too many students waste thousands of hours in their lives pursuing this.

Here's the problem: well-rounded students don't do anything particularly well. They're not team captain of a national-ranking soccer team, or head of a new statewide nonprofit, or concertmaster of a leading orchestra. This means that none of what they do is truly impressive.

To put it bluntly, "well rounded" means "mediocre at everything." Jack of all trades, master of none.

By being a jack of all trades, you risk being master of none.

Mediocre people don't end up changing the world. They might be great low-level employees. They'll be followers, not leaders. But top schools like Harvard and Stanford want to train leaders who will change the world.

(Is this rubbing you the wrong way? Let me pause here. Remember above what I said about possibly sounding elitist? There's nothing wrong with being a jack of all trades and master of none. You might not even be that interested in success or achievement as traditionally understood by society. That's completely fine. It might be the best way to make you happy, and if so, that's the path you should take, no matter what anyone says. But top schools aren't looking for people like this. And since that's our goal right now, excuse me for being blunt.)

Think about this—did the New England Patriots care about whether Tom Brady could do math? No—he just needed to be a great quarterback and team leader. Few other things matter.

If you break your arm and need surgery, do you care that your surgeon has a fly-fishing hobby? Likely not—you just want her to be the best surgeon possible so she can fix your arm.

Does being well rounded sound like your plan? Be careful. You're going down the wrong path, and you need to fix your course before it's too late.

Here's why students make this common mistake: because they're not yet in the real world, they have a warped impression of what it takes to be successful. In a young teenage mind, it probably seems like to be successful in the future, you should be successful at everything—you need to be charismatic, be super-smart in all subjects, have a great smile, and be a great public speaker.

Let me clear up this misconception with a lesson I learned the hard way.

#3: What Does It Really Take to Make a Difference in the World?

In a word, focus. Relentless focus.

The world has gotten so specialized now that the days of the successful dilettante are over. Each field has gotten so developed, and the competitors so sophisticated, that you need to be a deep expert in order to compete.

If you become a scientist, you're competing with other scientists who are thinking about the same problems all day, every day. And you're all competing for the same limited pool of research money.

If you're a novelist, you're competing with prolific writers who are drafting dozens of pages every day. And you're all competing for the limited attention of publishers and readers.

This applies to pretty much every field. There really is no meaningful area that rewards you for being a jack of all trades (I would argue that early-stage entrepreneurship comes closest, but it's still far away).

If you don't have your head 100% in the game, you're not going to accomplish nearly as much as those who are 100% committed. This is what it takes to make a revolutionary difference in the real world.

This does not mean you can't have multiple interests. Successful people often have wide-ranging interests and do especially interesting things at the intersection of them. I'm just saying that it's harder to be a true Renaissance man now than it was during the Renaissance, when much less was known about the world. Life necessarily has tradeoffs—the more areas you try to explore, the less deeply you'll explore any one of them.

Note as well that this does not mean colleges expect what you focus on now to be your focus for the future. This is a common worry among high school applicants. But the reality is, colleges know you'll change, and they want you to change. You might be a top ballerina today and a neurosurgeon tomorrow. What's more important is that you demonstrate the capacity for success.

If you work hard enough and have the passion and drive to become a top ballerina, the colleges know you'll be much more likely to succeed in whatever else you put your mind to later because the personal characteristics that earn success are pretty common in all fields.

To find evidence of this, we looked at what Princeton's admissions office had to say:

"Instead of worrying about meeting a specific set of criteria, try to create an application that will help us see your achievements — inside the classroom and out — in their true context, so we can understand your potential to take advantage of the resources at Princeton and the kind of contribution you would make to the Princeton community. Show us what kind of student you are. Show us that you have taken advantage of what your high school has to offer, how you have achieved and contributed in your own particular context ... We want to know what you care about, what commitments you have made and what you've done to act on those commitments."

Clearly, it's important that you show your capacity for achieving success. We'll cover this a lot more in the next sections.

Once again, if you're not that interested in making a huge difference in the world, that's completely fine. Many people don't. But you'll have to accept, then, that top schools won't be that into you.

Back to your application now—what does all of this mean for you? Essentially, you need to prove that you're capable of deep accomplishment in a field. This is what your application ultimately must convey: that you are world class in something you care deeply about.

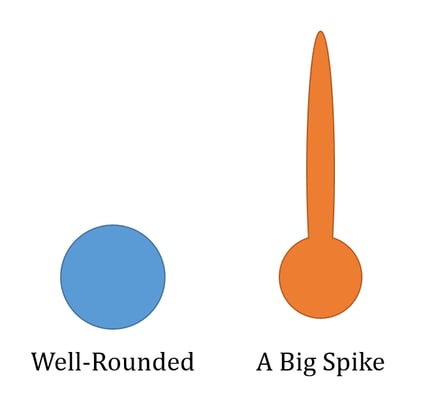

In other words, forget well rounded—what you need to do is develop a huge spike.

#4: What Is a Spike and How Can You Develop One?

This is really important, and it's my biggest point in this entire guide.

A spike is what sets you apart from all other applicants. It goes against the spirit of simply being well rounded. By nature of being unique, you don't fit in with all of the other well-rounded applicants; you do something that truly stands out in a meaningful way.

This spike requires consistent effort, focus, discipline, and passion to grow. Ideally, this spike is what makes you world class and makes colleges think you're going to accomplish great things in your lifetime.

A spike can come in a lot of forms depending on your field of interest. If you're a scientist, it might mean doing compelling, original research at a local college. If you're a writer, it could be publishing a book. It could also mean competing at the national level as an athlete, or creating a successful app as a programmer.

What we're looking for is something truly impressive that is difficult to do and sets you apart from the bargain bin of well-rounded students.

If you're dismissing my advice because you think, "There's no way I can achieve something that unique and that notable," please keep reading. It's not as impossible as you think it is, and I'm willing to bet you have the core capabilities for doing this.

What most students get wrong is where they spend their time and what they prioritize. They also give up far too early—before they've achieved significant results and before they've crossed the major hurdles that precede success. I'm going to show you below how you might be wasting 1,000 hours every year on things that don't matter.

Don't let fear about your own limitations hold you back into complacency.

Later on, I'll explain a lot more about what a big spike looks like, and how you can figure out what a good spike for you is based on your personal interests. Keep this image in mind as we go through the rest of this guide.

You can tell from my picture above that the round part of the big spike is smaller than that of the well-rounded ball. This is intentional.

It's OK to be unbalanced if you develop a big spike. Since colleges care more about whether you'll achieve something great in your lifetime, by proving that you can do so in an area of interest, colleges will care less if you fall short elsewhere.

Unbalanced is OK in college applications—as long as you've got your spike.

Unbalanced is OK in college applications—as long as you've got your spike.

For example, if you're a science whiz, you do not have to be an amazing writer. Heck, you don't even have to take AP English. MIT won't care that you didn't!

This is a really hard point for high-achieving students to grasp. "What do you mean I don't need to get straight As and work 5,000 volunteer hours and also play basketball and tennis?"

Let me tell you from personal experience: having met a lot of incredibly talented people in my life, many very successful people are incredibly unbalanced. They don't fit your profile of well rounded at all.

Brilliant scientists make deep achievements by pushing the boundaries of our understanding of the natural world, but some are hapless in the rest of life. The stereotype of the brilliant, social-misfit scientist is actually sometimes spot on.

In contrast, athletes who have incredible control over their body and an innate understanding of physics might not be able to solve actual physics problems that well.

These are relative extremes, and you'll likely be more balanced than this. But the point is clear: people who focus on something specific, especially something they're passionate about, end up making the greatest impact. In turn, this means that focusing on something specific right now can illustrate your potential for achieving even greater things later on.

We've covered a lot in this section. To sum up, here are the major takeaways:

- Top colleges want students who are going to change the world.

- The best predictor of future success is previous success.

- Because future success requires deep achievement, you should demonstrate deep achievement in high school.

- Forget well rounded—you want to develop a huge spike.

Sidebar: Sometimes, a natural reaction to this is that you know you're capable of a lot, and that your past achievement (or lack thereof) doesn't reflect your potential to change the world.

Your spirit is fantastic. But the rest of the world doesn't see it the way you do.

Let's imagine you're getting knee surgery, and your surgeon is fresh out of medical school. "I'm fully capable of doing the best knee surgery, and I care a lot about your well-being. I'll do everything I can do make sure you do great."

You say, "Sure—but how many surgeries have you done before?"

"This is my first one. I had a lot of opportunities to practice knee surgeries before, but I didn't take them. But I promise you that I'll do well this time around."

Red flag. You would probably recoil and ask for someone with more experience. Colleges treat this the same way.

Between a person who's passionate but hasn't shown achievement and a person who's similarly passionate but has shown deep achievement, Stanford will take the second one. Every. Single. Time.

That's why prior achievement is so important.

Part 3: Busting a Myth: "School Admissions Are a Crapshoot for Everyone"

You might've often heard that school admissions for the Ivy League and other top schools is "just a crapshoot." Or perhaps you've heard a different variation of this phrase: "It's just random." "Accept your outcome and move on."

Here's the truth: admissions are only crapshoots for the marginal person that the school wants to admit (i.e., the person that the school is indifferent about admitting and can take or leave).

Let's pick a specific school: Harvard. This top Ivy League institution gets around 43,000 applications every year and has a mere 5% acceptance rate. Obviously 5% sounds really low. But admissions is not a random lottery. Many people make the conceptual mistake of thinking that everyone who applies has a 5% random chance of getting in.

The truth is that everyone who applies has a different chance of admission. If you're a true superstar, your admissions chance is closer to 90%. If you're a weak applicant, your admissions rate will be near 0%.

Let's work through some numbers. I'll start off with some round numbers for easier math, and then we'll show you the proof from Harvard's admissions statistics.

Let's say there are 5,000 "world-class" applicants in the country. These are all students who have achieved great things in their primary areas of interest, whether that's social work, writing, scientific research, the arts, or athletics. four to five million high school students graduate every year, so world class means being in the top 0.1% of all people.

Of the 5,000 world-class students in the country, 1,000 of them apply to Harvard. (Not every world-class person is applying to Harvard because everyone's interested in different schools, like Princeton, MIT, Yale, Stanford, Columbia, state schools, etc.)

Remember that Harvard receives 43,000 applications, so 42,000 applications are not world class. For the sake of simplicity, let's say 37,000 of these are strong and qualified applications, and 6,000 are just totally unqualified and applying for the moon shot.

Here's what the breakdown of applicants looks like:

|

Applicant Status |

# of Applicants |

|

World class |

1,000 |

|

Strong, well rounded |

37,000 |

|

Not qualified |

6,000 |

Harvard gives out about 2,000 acceptances each year. Here's where it gets interesting.

Of these 2,000 acceptances, 900 acceptances go to world-class applicants. This is fair—Harvard wants to fill its class with the best people possible, so it gives every world-class applicant a shot at going to Harvard. At the same time, the school rejects 100 world-class applicants because they're huge jerks and have terrible personalities that don't mesh well with the school.

Now, Harvard has 1,100 acceptances remaining. This is still a lot of students, but remember that there are a lot more applicants who are not world class. As a result, the admissions rate goes way down.

Let's tabulate the acceptances for each class and the corresponding admissions rate:

|

Applicant Status |

# of Applicants |

# of Acceptances |

Admissions Rate |

|

World class |

1,000 |

900 |

90% |

|

Strong, well rounded |

36,000 |

1050 |

2.9% |

|

Not qualified |

6,000 |

50 |

0.8% |

It should be clear to you that for the group of world-class people, the chance of admissions is far higher.

When people look at the 5% overall admissions figure, it seems really hard. It seems like everyone has a 5% chance of getting in, which is why it's said to be a crapshoot.

This is totally false. If you're world class, your admissions rate is much, much higher than 5%.

But if you're in the second tier, then top college admissions will be a crapshoot.

(I know what you're thinking at this point—"I'm not world class, and I don't know how to be." I don't expect you to suddenly become an Olympic swimmer or a science prodigy. But there are specific actions you can take to make deep accomplishments and avoid being merely well rounded. More on this later.)

Data from Harvard Admissions Supports This Premise

These aren't just my personal ideas. Harvard's admissions statistics corroborate them. In the Asian-American discrimination lawsuit a few years back, Harvard was forced to release private admissions documents on how it graded applicants and admitted them based on their grades.

Here are the bullet points:

Harvard rates each applicants a score of 1-6, on the following categories:- Academic

- Extracurricular

- Athletic

- Personal

1 is the highest possible score. It is rare - less than 1% of applicants earn a 1 in any category.

A score of 1 indicates deep achievement. Here's Harvard's description of what a 1, 2, and 3 is in each category:

- Academic:

- 1: "Summa potential. Genuine scholar; near-perfect scores and grades (in most cases) combined with unusual creativity and possible evidence of original scholarship."

- 2: "Magna potential: Excellent student with superb grades and mid-to high-700 scores (33+ ACT)."

- 3: "Cum laude potential: Very good student with excellent grades and mid-600 to low-700 scores (29 to 32 ACT)."

- Extracurricular:

- 1: "Unusual strength in one or more areas. Possible national-level achievement or professional experience. A potential major contributor at Harvard. Truly unusual achievement."

- 2: "Strong secondary school contribution in one or more areas such as class president, newspaper editor, etc. Local or regional recognition; major accomplishment(s)."

- 3: "Solid participation but without special distinction. (Upgrade 3+ to 2- in some cases if the e/c is particularly extensive and substantive.)"

2 is where a lot of strong well-rounded, locally renowned students sit. 1 is where the world-class students sit. (Nuance: Harvard does give +'s and -'s, so it's possible to get a 2+, and that will make you much stronger than a 2-.)

Earning a 1 in any single category is rare, but dramatically raises your admissions rate.

- Getting a 1 in even just one section is rare (<1% of applicants get it). It's very rare for one person to get 1's in multiple sections.

- If you get a 1 in any section, your chances of admission are between 50-70%, depending on what you earn it in.

- Getting a 2 in any single section is much more common (20-40%) with a much lower chance of admission (between 12-26%)

Here is the legal court filing source for this data. I've extracted the key tables for you, showing the application statistics across 6 years, Classes of 2014 to 2019. The key point is that most students get a score of 2-3 in every category, but the 1's get admitted at rates of 50-70% - far higher than the overall admissions rate of 7.4%. (If this seems high, reminder that this is older data running up until 2015 admissions decisions - the overall admissions rate is now down to below 4%).

Academic Rating

| Academic Rating | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Applicants | 5969 | 17690 | 58061 | 60468 | 650 |

| % of Population | 4.2% | 12.4% | 40.6% | 42.3% | 0.5% |

| Admitted | 4 | 175 | 2429 | 7500 | 450 |

| Admit rate | 0.1% | 1.0% | 4.2% | 12.4% | 69.2% |

Extracurricular Rating

| Extracurricular Rating | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Applicants | 952 | 4639 | 102784 | 34038 | 425 |

| % of Population | 0.7% | 3.2% | 72.0% | 23.8% | 0.3% |

| Admitted | 52 | 187 | 3957 | 6147 | 215 |

| Admit rate | 5.5% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 18.1% | 50.6% |

Personal Rating

| Personal Rating | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Applicants | 24 | 604 | 112513 | 29660 | 37 |

| % of Population | 0.0% | 0.4% | 78.8% | 20.8% | 0.0% |

| Admitted | 0 | 1 | 2846 | 7687 | 24 |

| Admit rate | 0.0% | 0.2% | 2.5% | 25.9% | 64.9% |

In summary - this is clear, hard, legally binding proof that stand-out students are admitted at over 15x the rate of the rest of the applicant pool.

Some more numbers to put this into perspective. Out of 42,749 applicants for Harvard's Class of 2022,

- 8,000 had perfect GPAs

- 625 had a perfect score on ACT; 361 had a perfect 2400 on SAT

- 3,500 had perfect SAT math; 2,700 had perfect SAT verbal.

That's a lot of high achieving students. But these scores aren't enough to get a 1. As you see above, only 0.5% of applicants typically earn a 1 in the academic score, or around 210 students.

There are just too many students who perform at the top 1% of academics nationwide. With 4 million high school students per year, 1% is 40,000 students!

To get a 1 Academic rating requires much more than 99th percentile GPAs or SAT/ACT scores - these are, unfortunately, relatively common.

If you want to do more reading: Here's a useful summary on Reddit. Here's a similar one from The Washington Post. Here's my writeup and analysis. Here are the raw legal documents you can spend hours reading through.

Why Being Well Rounded Hurts, Part 2

From the data above, you can see how many more well-rounded students there are than truly stand-out, world-class students.

Well rounded is boring. You have nothing special about you and nothing that sets you apart from other well-rounded people.

If you're looking at a bargain bin of basketballs at Walmart, they'll look identical. They're all round and seem equivalent to each other. Some might have slightly higher dimples than others. That's it.

A bunch of well-rounded applicants, grouped together. How do you tell them apart?

This is what well rounded does to you. You won't stand out from other students. Everyone's doing the same stuff as everyone else—taking a decent number of AP classes, joining uninspiring extracurriculars such as yearbook, volunteering at the local hospital, etc.

And because of the vast numbers of well-rounded people out there who don't have anything remarkable about them, you have a tiny chance of getting in.

Here's another painful fact about being well rounded: the school doesn't really care if you get in or not, compared to the next comparable applicant. This is what I mean by "marginal acceptance."

Here's an exercise: I want you to think about the very best meal you've ever had.

Have one in mind?

It probably sticks out in your mind for specific reasons. Maybe the food was incredible, or you had amazing company, or it was a really special occasion. But your mind went to this #1 meal for a reason.

It's clearly even better than the 2nd best meal you've ever had. That best meal means a lot to you.

Now think about the 20th best meal you've ever had.

...

...

Waiting ...

You probably need to think really hard about what this even is, even though you've already eaten 20,000 meals in your lifetime. The 20th best meal is in the top 0.1%! But still, it's incredibly hard to remember.

And how much more do you care about the 20th vs the 21st best meal? Likely not very much.

Admissions works the same way. Top colleges care a lot about their superstars, and they want to make sure they don't miss any of them because this can dramatically change the flavor of their class. They don't want to miss the next Hemingway or Mark Zuckerberg. This is why the admissions rate for world-class people is so high.

But the rest of the class? It doesn't matter as much. Of the 1,100 well-rounded candidates from the table above, Harvard could randomly choose 1,100 from the pool of 33,000, and Harvard probably wouldn't change all that much.

This is why you'll often hear admissions officers from schools like Yale and UPenn say, "Admissions are really hard—there are way more qualified applicants than there are students we can support. We have to make tough decisions."

They're talking about the well-rounded students. They're not talking about the superstars with big spikes, who are usually clear, automatic acceptances.

When you compare well rounded with well rounded, it truly is a tough decision. How are you going to evaluate one bargain bin basketball against another?

This Is the Crapshoot—and the Crapshoot Sucks

Having talked to admissions officers and witnessed admissions discussions at Harvard, I find it shocking how random admissions can be if you're a marginal acceptance.

Admissions officers often go "by gut." Something about your application can pique their interest and focus their attention. Equally likely, something about you might give your reader a bad taste in her mouth. And now, because your reader presents you to the admissions committee, suddenly you're fighting an uphill battle.

To be honest, if you're indistinguishable from other candidates, your admission doesn't really matter to them. Admissions officers do honestly want to create the best class possible, but at the end of the day this will mostly sort itself out. So unless you really strike a chord in the reader, she won't fight that hard for you.

This is the critical difference between students and colleges in how they view a single application. In your mind, your application is a special snowflake, constructed carefully piece by piece over years of your life and deserving hours of scrutiny by the school arbiters.

In their minds, they're sorting through literally thousands of applications. World-class standouts are clear. From the second tier bin of comparable, undifferentiated applicants, their choice doesn't matter a whole ton. It's hard to tell who's better among them at this point, and everyone seems equally qualified, so largely they just go by their guts and choose people they like a bit better. This is the crapshoot.

You want to avoid the crapshoot. The crapshoot is not fun and it's not for you.

Tell Me Whether This Story About Your Life Sounds Familiar

In my work at PrepScholar, I work with thousands of students across the country. This is one thing I hear over and over again:

"I just don't have any more time in my schedule. I have a bunch of AP classes, sports practice, marching band, and volunteering. I get home late and work on homework until 1 am. I'm barely struggling to hang on, and it all feels like it's going to unravel at any second."

Does this sound familiar? Do you see yourself fitting this profile?

I'm sorry that you're stressed out. If you're a high-achieving student, high school is tough because admissions gets more competitive every year.

Unfortunately, most of what you're spending your time on is probably not raising your chances of getting into Princeton.

And most likely, you don't really love most of what you're doing. Which makes for a pretty miserable time.

The good news is, it's not too late for you. I'm going to talk about how you can cut out the crap and build a much stronger application while spending your time on things you really care about.

Part 4: What Does All of This Mean for Your Application?

Remember my biggest piece of advice: forget well rounded. You're looking to develop a huge spike.

Let me repeat what I said earlier. That spike is what sets you apart from the other applicants. That spike makes you hard to fit into the bargain bin of well-rounded balls. This spike requires consistent effort, focus, discipline, and passion to grow. Ideally, this spike is what makes you world class and makes colleges think you're going to accomplish great things in your lifetime.

This spike comes in a lot of forms depending on your field of interest. If you're a scientist, it might mean doing compelling original research at your local college. If you're a writer, it might mean publishing a book. If you're an athlete, it might mean competing at the national level. If you're a programmer, it might mean creating a successful app.

What we're looking for is something truly impressive that's difficult to do and sets you apart from the bargain bin of well-rounded students.

Make no mistake—this is hard to achieve. That's why it's so special. There is no secret that will suddenly create something world class for you. But it's also probably closer to your reach than you think.

Many students try to develop a spike or "hook" in their applications. But where they fail is that they don't put in enough time, they don't optimize the way they achieve their goals, and they give up when the going gets rough, before they achieve something meaningful.

As I'll soon explain, often the way you will demonstrate this spike is in your extracurriculars.

What Does This Mean for the Rest of Your Application?

Aside from extracurriculars, you also have to worry about your GPA, SAT/ACT scores, letters of recommendation, and personal statements.

Your application's job is to support the story around this spike. Every piece of your application should be consistent with this story.

This leads to my second biggest rule: you do not need a perfect application all around.

Instead, focus on your strength—that is, your spike—even at the expense of other aspects of your application.

Are you a science fanatic? Then you need to show that you're super strong in math and science; it's OK to be weaker in English.

Are you a writer who can't stop crafting stories? Show that you have great talent and achievement in your writing—you don't have to ace calculus.

Are you being recruited for a sport? Then you don't need to be great at academics at all—just good enough to get through college. Focus the rest of the time on getting better at your sport.

Remember, no one cares that Tom Brady isn't a mathematician or that Mark Zuckerberg isn't a gymnast.

That said, you can't totally fail in the rest of your application. There are some things you can never do, like show a serious ethical lapse or have a terrible personality. No amount of achievement will overcome the perception that you're a huge jerk who no one likes to be around. (Colleges want to admit students who will be positive additions to their communities!)

You also need generally strong academics. Academics at top schools isn't trivial, and colleges want to make sure you can survive comfortably without too much trouble. You usually can't apply successfully with a 20 ACT score unless you do something truly groundbreaking. (I talk more about academic requirements in the FAQ below, so be sure to read to the end.)

So you should look generally competent in the rest of your application, and you should take challenging classes in your area of interest. But overall, colleges don't care that much about things that aren't your single strength. Once again, your ability in your passion contributes more to your success than being well rounded does.

What Do Strong Spike Applications Actually Look Like?

I've been talking abstractly for a long time. Let's make this more concrete.

For illustration, we'll walk through two example applications for people with very different application profiles. For these, we'll look at the major components of the application:

- Grades/GPA

- Test Scores

- Extracurriculars and Awards

- Recommendation Letters

- Personal Statement

In general, extracurriculars are where you will develop your spike. This is where you can truly stand out, since the other components are standardized between most applicants and don't differ much. But as you'll see, the other pieces will all be part of your consistent story.

Profile 1: The Science Superstar

This student (let's call her Sarah) is a science whiz. A current high school senior, she's deeply interested in physics and ultimately plans to do a PhD and conduct research in particle physics. Here's what her application looks like:

Grades/GPA

No surprise—Sarah has aced all her science coursework. She's taken all the major AP science and math courses (Biology, Chemistry, Physics C, Calc BC) and gotten As in them.

She's not the best writer and finds it hard to focus time on things that don't naturally interest her, so she's gotten Bs in a few English and history courses. This brings her unweighted GPA to 3.95—not perfect, but still strong.

Test Scores

On her ACT, Sarah started out with a 32. She found a good tutor from her local area (Boston for Sarah) and she ended up scoring 34 on Math, 36 on Science, and 32 on both English and Reading. For her AP exams, she's scored 5s on all math and science tests, and 4s on the AP English and US History tests.

Extracurriculars and Awards

This is where Sarah really shines. Her largest achievement was participating in the US Physics Olympiad study camp, which selects the top 20 students nationwide after a series of demanding qualifying tests. These students are trained, and the top five represent the US at the International Physics Olympiad. She didn't get into the top five as a junior but hopes she will as a senior.

Sarah is also fascinated by science research and has worked in a biophysics research lab at her local college for the past two years. Throughout the school year, she spends 10 hours a week on research work but has also spent two months for the past two summers working full-time on research. Her research concerns the physics behind protein folding, with applications for infectious diseases such as HIV. She's participated in nationwide research competitions, including the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair.

Sarah is also a member of her school's Science Bowl and Science Olympiad teams, though these haven't moved beyond the state level.

In her free time, Sarah enjoys skiing and reading.

Recommendation Letters

Sarah has letters from her AP Chemistry teacher, her AP Calc BC teacher, and her camp supervisor at the US Physics Olympiad study camp. These are some snippets from the letters:

"Sarah is endlessly inquisitive, always diving deep beyond the textbook to find out the limits of what we currently know in science—and in the process stretching my knowledge as well."

"Sarah also has an incredible warmth of personality—she was always happy to help her neighbors figure out their mistakes after receiving their test scores. I noticed a halo effect in which people who sat around her tended to do better than the average student in class."

"One of the most passionate and impressive students I've seen in my entire teaching career."

Personal Statement

In her personal statement, Sarah talks more deeply about her interest in physics on a philosophical level, and how her interests have evolved over the years. It provides a nice complement to her list of achievements to convey what makes her tick.

Summary Assessment for Sarah

Sarah is clearly a very strong candidate that all top colleges would be happy to have as part of their class. She's created a spike in her application by competing at the highest levels possible and making deep achievements in her field. From her competitions, it's clear that she's world class in her abilities. She also seems to be a pretty cool person as evidenced by her letters of recommendation and personal statement.

The most important point from this illustration is that she's not "well rounded" in the sense that most students try to achieve. She isn't that strong in the humanities, and this shows in her grades and test scores. She also doesn't have filler activities that "well rounded" students try to stuff in, such as hundreds of volunteer hours, Future Business Leaders of America, or a musical instrument.

Instead, she's focused her time to deepen her area of interest. While others are spreading themselves thinly by covering all their bases, she's diving deep into science and physics.

Let's go through one more example of someone with a huge spike in his application.

Profile 2: The Burgeoning Writer

Maxwell has loved crafting written language for a decade. Starting off with simple fiction as a middle schooler, he's started writing more complex works as he's acquired more experience and learned more about himself. He devours literature nearly every chance he gets.

Grades/GPA

Maxwell excels in all things related to language. He aced AP English Lit and English Language, and he's taken several electives related to writing.

For his other subjects, he's at standard grade level. He'll take pre-calculus as a junior. He's taken a few regular science classes but doesn't plan on taking APs for these subjects. His GPA is a high 3.9.

Test Scores

Maxwell scored 1400 on the SAT: 800 on Evidence-Based Reading and Writing, but 600 on Math. He also scored 5s on AP English Lit and English Language.

Extracurriculars and Awards

Once again, this is where Maxwell shines. His free time is focused around writing in all forms. Here are a few of his notable accomplishments:

- He's been published in the top three periodicals for teen writers nationwide.

- Since freshman year, he's entered dozens of writing competitions for high school students and won top prizes for a few of the most prestigious ones.

- He runs a popular blog in which he comments on high school life with a satirical bent. Some of his articles have been reposted by popular publications such as the Huffington Post, where they've gone viral and received hundreds of thousands of views.

- He started a writing club at his high school with the idea that students can share their work and get peer feedback on their writing. It grew to 30 students, and students at other high schools have become interested in participating. As a result, Maxwell has cobbled together an online platform on which students can post their works anonymously and get feedback from readers. He hopes he can expand the platform's reach to the rest of the country to establish a peer network of writers.

Recommendation Letters

Maxwell asked for two letters from his teachers, one of whom is the supervisor of the club Maxwell started. They both speak to his genuine passion for writing and initiative in pursuing his art in a school that doesn't have a lot of structure to support it. They also comment on his cheery personality and how he's a class favorite.

Personal Statement

Maxwell writes a statement about his process for writing, and how it's symbolic of his general approach to life. Of course, because of his deep experience in writing, his statement also stands out in its eloquence and vividness.

Summary Assessment for Maxwell

Clearly, Maxwell is an accomplished writer. He's honed his craft over years and is now producing work that's recognized by publications. He also shows his passion and initiative by spotting a need—i.e., peer feedback for high school writers—and creating a group around it. His accomplishments are world class; few other people his age who are interested in writing have achieved as much as he has.

Once again, though, he doesn't have a perfect application. He's not strong in math or science, and he's not taking the most challenging courses in these fields. His SAT score is below average for a school like Harvard. But his spike—his writing-related achievements—more than make up for this.

Interested in seeing what MY spike was?

Here's my ENTIRE college application. I take you through every single page of the successful application that got me into Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, MIT, and more.

I show you my entire application, including my Common App, personal statements, letters of recommendation, transcript, Harvard supplement, and more.

I also provide strategic comments on how each piece fits together to make for a compelling application.

Furthermore, you'll see what I considered weaknesses in my application, and how I could have improved it further.

If you've liked my advice so far, you'll love seeing my complete Harvard application.

Recapping Application Profiles

I hope the point is clear now. A big spike is truly impressive. It requires innovative thinking, hard work, passion, and focus. That's why these achievements sound so impressive to you—they wouldn't be so impressive if literally every student could do them. But they're also easier to achieve than you think, as long as you structure your life and time the right way.

Furthermore, I want to stress that you do not need to be a perfect applicant to get into Harvard or Yale. In fact, there really is no such thing as a perfect applicant. Why? Because by focusing deep on something, you'll ultimately need to make compromises elsewhere.

There is no one in the world who is an Olympic athlete, a Nobel laureate, and a legendary rapper, all at the same time. So stop feeling bad about yourself. Focus on what you like doing and what you're good at, and keep doing that.

The deeper you go in one passion, the more that compensates for weaknesses in other areas. The shallower you go, the more you have to compensate by being well rounded. And, again, the more well-rounded you are, the deeper you fall into the crapshoot.

Sidebar: After saying all of this, I imagine you might say, "Allen, I know someone from my high school who got into Princeton and wasn't world class the way you're describing."

Did that person apply to multiple top-10 schools, AND did she get into most of those schools?

If so, I would argue that she was world class. When multiple schools want you, you're doing something that really sets you apart and makes each school take notice. You should ask her what she did and see whether I'm right.

If not, then I would say she was one of the lucky ones who got in as part of the crapshoot. Something about her caught the eye of an admissions officer at Harvard, which got her in. This didn't happen at other top schools, so she didn't get in.

I'm not trying to be a snob here. I'm sure she's an awesome person, she's very competent, she deserves her success, and she's going to do great in life.

But if she had a stronger record of achievement, more schools would have wanted her.

Once again, if you're aiming for top schools, you don't want to be part of the crapshoot. You want to try to build yourself to a level at which Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, and Stanford are all dying to give you a chance to attend their school.

Part 5: OK—So Now What Do I Actually Do, Allen?

I know all of this is overwhelming. These applicants have accomplished so much that it seems like only something you read about in the news, not something you can accomplish yourself.

The reality is, there are thousands of students who achieve things like this in different fields, and you can be one of them. There's no question that it takes focus, discipline, competency, and passion. But it actually takes less raw talent than you think. Society in general overvalues cleverness and undervalues pure determination and hard work.

Just by taking the time to read all the way down here, you're showing that you care more about your personal success than most other students do. This means that you can do it. I'm really not BSing you or trying to blow up your ego. You can make this happen through sheer force of will and structure in your life.

To make this concrete, we're going to do a two-step exercise.

Steve Jobs: someone who was never afraid to think big.

Step 1: Think Big—What Can Be Your Spike?

I want you to take a moment and think ambitiously, freed from the constraints you're facing in your life.

Let's say you had to go to school but had zero homework, and you didn't need to do any studying or test prep. This gives you about 40 hours every week outside of school.

What do you think you could achieve in this time, over a full year, by pursuing something you are really interested in? Think big.

Here are a few examples:

- Like a particular academic subject in the sciences or humanities? Try to find a national level competition that you can rank well in. Find out how to excel in this competition, and work hard to meet the challenge.

- In the sciences, there are the well-known Olympiad competitions, as well as Science Bowl and Science Olympiad.

- In the humanities, there are competitions for speech/debate and writing (e.g., essays, poetry, etc.).

- Passionate about a unique cause? Try to start a club or nonprofit group. Use methods that you know well to raise awareness, like social media and Kickstarter. Imagine if you started a viral phenomenon like the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. Try to do something good, in a quantifiable way—consider the number of people you could help, the number of students you could teach, or the amount of money you could raise. Imagine recruiting your friends to help you out and growing this to a nationwide effort.

- Interested in computer programming? Technology barriers have been lowered like never before. Think of a useful tool you'd want in your everyday life, build it, and then publicize it. How about releasing a mobile app and putting it in the App store?

- Considering becoming an academic? Try to organize your own research internship at your local college. Approach professors with a passion for learning and a long-term commitment, and they will be far more likely to consider training you.

- Have a hobby you enjoy? Think about how you can take it to a more impactful level. Can you showcase your expertise in this hobby somehow and achieve recognition? How about spreading your passion to other interested people by acting as a mentor?

- Don't worry if your true interest seems silly. Interested in makeup and beauty products? Consider starting a high-quality YouTube channel catering to a niche audience, such as high school students or budget-strapped buyers. Imagine if you had 100,000 subscribers. Or what about video games? What if you started a nationwide high school gaming tournament?

These are just the more obvious suggestions—there are a lot more better ideas you can come up with on your own.

You know way more about your interests than I do, and you know what's considered exemplary in these fields. You can also come up with unique opportunities that no one else can. These are not only massively rewarding and fun for you to work on, but also truly impressive for your college application.

The key here is that you need to show something of meaningful achievement. You don't want to just create a random YouTube channel—you want to get to 100,000 subscribers. You don't want to just make a mediocre app—you want to get it ranked in the top #100 in the App store.

Again, think big.

Step 2: What Are You Wasting Time On?

Now, of course, the bigger you think, the more daunting the ideas seem to implement.

The good news is, you're likely wasting a ton of time on things that you don't enjoy and that aren't improving your college application one bit. If you carve these out of your life, you'll have a ton of free time you never realized.

Here are a few major time sinks that most students fall victim to:

#1: Classes That Don't Fit Into Your Story

This is probably the biggest, most insidious time cost, and the most controversial suggestion in this group.

The "well-rounded" applicant hears of students taking 10 AP courses and thinks he must replicate this. He'll spend six hours each day slogging through homework, thinking that 10 AP courses must be way better than eight.

Wrong, wrong, wrong.

Coursework has a property of "diminishing marginal utility." This means the more AP classes you take, the less each additional AP class is going to add to your application. Compared to zero AP classes, one means a lot. Compared to one AP class, two mean a lot. But eight AP classes is barely better than seven.

Here is a hypothetical illustration:

This is an economic concept that applies to a lot of things in life, whether it's times wearing a new outfit, number of kisses from your crush, or times gone to Disneyland. Most things tend to follow this curve. AP classes are no different.

How much time does an extra AP class cost you? Let's say beyond the normal class, there's an extra five hours per week of homework and studying for tests, and 36 weeks in a school year. Let's say in preparation for the AP test, you also study an extra 50 hours. In total, this means an extra 230 hours.

230 hours is a lot of time in one year. To put this into perspective, that's six weeks of full-time work for a normal 40-hour-per-week job. (From personal experience, 230 hours is also many times more than most students spend studying for the SAT/ACT—which is a mis-optimization, given how important the SAT/ACT is and how unimportant an extra AP test is.)

From your passion project from step 1, how far could you get with an extra 230 hours of time? It's likely a lot.

The number of hours can well exceed this if the class is especially difficult at your school or the material's really hard for you. It might go up to 400 hours in one year.

And if you avoid taking multiple AP classes that you really don't have to take across multiple years, this might end up amounting to 1,000 hours. That's a ton of time, and enough to get proficient at pretty much anything you want to learn.

If you hate biology, don't take AP Biology. It's as simple as that. Don't be pressured into it by your high school counselor, friends, parents, or college advisers. It's not going to fundamentally change your application—what can is what you do with the extra time you save.

#2: Unhelpful Extracurriculars

There are a lot of extracurriculars that suck up a lot of time and that really add nothing to your application. Here are some common examples:

- Volunteering: Many students spend hundreds of hours per year volunteering (imagine you volunteer three hours per week for 50 weeks). Most people do it because they feel like they have to. And most do it in a way that does the opposite of standing out. Tens of thousands of students volunteer at local hospitals, wheeling patients around or delivering flowers. It's not at all special and takes little innovation on your side, so you get no extra points for doing this.

- Athletics: This is a super heavy activity. Between daily practice and weekly matches, you can spend hundreds of hours per year on sports. However, if you're not team captain or a standout player (meaning you rank at state level or higher), this activity does very little for your application.

- Instrument Playing: Marching band can take multiple hours per week for practice and competitions, as can extracurricular orchestras. Furthermore, you're probably also practicing the instrument several hours every week. Unfortunately, if you aren't section leader or concertmaster, you're not impressive. Think of all the thousands of youth orchestras and marching bands out there and how many concertmasters/drum majors/section leaders there are. And you're not even one of them.

In other words, here are some signs that your extracurricular is a waste of time, as far as college applications go:

- It takes nothing special to do: If what you're doing can be easily done by anyone else, it's not groundbreaking enough to strengthen your application. For example, if getting your volunteer position means simply filling out a paper application, you're doing nothing special.

- You're not a leader, and you won't become a leader: If you're just a rank and file teammate or club member, you're not doing anything special. Once again, think about how many thousands of other organizations like that exist, and how many hundreds of thousands of other students are in the same position as you.

- You've maxed out your growth: How much time have you spent on this activity already? How much further will you get with another 50 hours? If the answer is "not that much," THOSE 50 HOURS ARE A WASTE OF TIME (as far as application strength goes). Sorry for the capital letters. This is a common fallacy in the many students we've work withed that it's frustrating when they don't see the logic here.

Let me expand on this last point more. A typical athlete will spend at least 500 hours per year practicing, exercising, and playing in games. This can be a valuable credit to their application. But if you've already spent 1,000 hours on a sport and won't do anything notable with an extra 50 hours (e.g., you won't win a championship or become team captain), those 50 hours can be better spent elsewhere.

The same logic goes for any of your other extracurriculars, such as volunteering, marching band, academic teams, etc.

I run into this problem a lot in the context of SAT and ACT studying. I see students across the country mis-prioritizing their time into things that they don't really care much about, and that don't improve their applications. Meanwhile, they're unable to work on their SAT/ACT scores for over 40 hours. This is a huge mistake since SAT/ACT scores respond very well to studying and have a disproportionate impact on your application for the time you put in.

Don't get me wrong—if you really, truly, madly, deeply enjoy the extracurricular, then keep doing it, even if it doesn't strengthen your application. If you feel like you have a real obligation to a group, they truly rely on you, and it's painful to think about leaving, keep doing it. It's good to do things that are meaningful to you and that make you happy.

But don't be in denial about your extracurriculars. The less time you spend on developing your spike, the less impressive it will be and the more you will become well rounded.

Examine all your extracurriculars carefully. If you're neutral about an extracurricular, and any of the three signs above apply, cut it out and use that time somewhere more impactful.

#3: Other Time Wasters

In your free time outside of school, homework, and extracurriculars, what do you do? Chances are, you watch YouTube, Snapchat, read Reddit, or something else "unproductive."

Few people are immune to this. In high school, I spent a lot of time playing video games, such as Starcraft, and chatting with friends. (This was before texting, so we used a program called AOL Instant Messenger. Good times.)

It was easy to waste a lot of time doing these things because they were fun and stress relieving. But they didn't help me get anywhere.

And to be honest, now that I have an adult's perspective, very few of those activities made a tangible, long-lasting impact on my life.

I'm not saying to cut off your social life and stop doing these other things. But do think about the extra value you get from every half hour you spend on these activities.

Again, the concept of diminishing marginal utility comes into play. If you go an entire day without talking to any of your friends, it's probably pretty painful.

When you talk to them, the first 10 minutes are awesome—"Did you see Mr. Robinson's new haircut? Oh. My. God." But an hour in, you're probably just talking about nothing in particular, procrastinating from doing other stuff because that other stuff seems annoying.

Fun, but not meaningful.

Challenge yourself and question what you're spending your time doing. Analyze whether you're getting that much out of every extra minute.

And have the willpower to shut it off and spend that time doing something you really care about.

How Much Time Can You Really Save?

Between all of the above, you can cobble together 1,000 hours per year. This is immense. It's equivalent to half a year of full-time work.

Apply this time to your dream project from step 1. In this time you could build a new organization, create a new mobile app, write 10 new essays to publish, or do any other notable achievement. You can do a lot with 1,000 hours.

Like I've said before, many students try to develop an application "hook," or spike, of some kind. But they don't spend enough time on it. They give up far too early before learning the critical best practices that make something work. They have too many distractions in their life with things that don't help their application.

Your aim is to accomplish more than the typical well-rounded student does by focusing your time and being smart about learning from your mistakes.

Done correctly, this kind of thinking requires you to have insight into yourself and your weaknesses. This is the kind of optimization in your life that you need to achieve deep success in high school and throughout your life.

While it may seem daunting or painful at first, I bet that you'll quickly enjoy the time spent developing your spike a lot more than the time you spent just being comfortable.

Again, if you're not willing to do this, that's fine. Just accept that you will be well rounded and will fall into the crapshoot. But if you're willing to put in the time, you will achieve great things.

The Importance of Passion—This Is NOT Helicopter Parenting

I know that developing a big spike can sound a lot like the result of "helicopter parenting." This is the much-maligned style of parenting wherein parents force their kids to become championship horseback riders, concert pianists, or beauty pageant contestants.

Helicopter parenting usually gets a bad rap because they're forcing their kids into doing something they don't want to do. This makes their kids miserable.

But the point of all my advice is to find something you're genuinely interested in. This is important because working really hard at something you don't care about can only get you so far.

For eight years, I played the violin and practiced for at least an hour a day. I wasn't passionate about this, and my mom had to watch my practice time like a hawk so that I actually did. At the end, I became fairly good at it, but I was nowhere near as good as our concertmaster who truly treated it as his passion. He worked harder at it and cared more about it, and to him I imagine each hour of practice was 10 times less painful and 10 times more effective than it was for me. This concertmaster went to Juilliard and is now a professional violinist—something I wouldn't have been able to achieve no matter how much time I put in.

When you have passion for what you're working on, you accomplish more, you think more creatively, and you become more resilient in the face of failure. When you really enjoy what you're doing, you think about what you're doing in your free time. You spend your spare time walking and using the bathroom thinking about the problems you're facing. You work harder because it doesn't feel like work. You're less likely to quit in the face of hardship, and that gets you through tough times. Because you're doing all of this, you come up with novel solutions and approaches that others don't.

This is important because in whatever area you choose, you are competing against people for whom the same area is their true passion. If it's not your passion, too, they'll leave you in the dust. Furthermore, colleges are typically pretty good at noticing when students are doing something only because they want to buff up their applications, not because they truly enjoy it.

So don't think only about how to get into Yale or how to get into Princeton. That's now how you should be orienting your energy. You should instead be thinking about how to achieve something great in your interests—getting into Stanford is a mere consequence of this.

Working on your spike should not feel miserable. It should feel joyful, that you're grateful you get to do it every day, regardless of whether you get into Harvard or not, regardless of whether you end up world-class or not. The ironic thing is this type of passion tends to produce the most impressive spikes. People who try to force world-class performance without real passion rarely get there (and I know, since I've forced this in a few different areas in my past).

It's hard to find a passion like this in your teens, I know. It's asking a lot. I didn't discover my true path until I was in my 20s (building businesses).

Is This Early Specialization and Is That Bad?

People who are afraid of early specialization (especially parents) worry that they're pigeonholing their kids into a narrow field at the exclusion of other things, and reducing their future options.

I get this concerns about this a lot. I address this problem in more detail in my FAQ and comments (keep reading to the end of the page) but it's so common and important I want to address it here.

Again, my advice in a nutshell is 1) to find your area of genuine interest and 2) to keep pursuing it to achieve as much as you can.

Building your spike does NOT mean you need to keep doing that interest for the rest of your life. Colleges expect you to change a lot as you go through college. What they are looking for is evidence of the potential for achievement, and that can be in any field you choose - even one that isn't consistent with your career down the line.

Building your spike does NOT mean you have to give up everything outside of that spike. Just because you want to focus on software engineering doesn't mean you have to give up your love of writing poetry as a hobby. But I do encourage focus and not spreading yourself thinly and equally - you usually get better results by making one thing your dominant things, and other things your strictly secondary things.

Personally, I think it's incredibly valuable to start thinking about interests early in life and pursuing them to achievement. Even if your interests change over time, you learn a lot of useful general skills:

- Learning how to learn and improve - if you get good at computer programming, a lot of the same principles apply to getting better at anything else - tennis, writing, composing music, etc.

- How to tell when you enjoy something and when you don't, and figuring out why

- How to overcome the obstacles and failures you'll inevitably hit when you push yourself to to your limit

Finding an area of interest that you can get obsessed about is an underrated skill. Most people hope to find what they're genuinely interested in, to find something that makes them feel their life is worth living. Unfortunately, many people don't discover this area of passion their entire life and die feeling a little empty - this is why you hear about mid-life crises and career misery. It is a real problem, one of life's most difficult problems because it is existentially important, but there is no formula to finding it and lots of headwinds against it (social pressure and mimicry, parents, finances, time constraints).

The Grand Overview: Getting Into the Ivy League

By this point, I hope my main points are clear. To bring it all together with step-by-step logic, here is the high-level overview of what I've talked about:

How top schools do admissions:

- Nonprofit schools exist to create value in the world.

- In the process of college admissions, schools want to maximize the value they create in the world.

- Thus, schools want to admit students who will eventually change the world.

- What does it take to change the world? Deep focus, passion, and competence.

- How do you predict which 17-year-olds are going to change the world eventually? Deep, prior achievement: prior success is the best predictor of future success.

What this means for your application: